During the 2024 Presidential campaign I wrote about the unremarked impact of losing the Iraq War on American politics. The failures of the Bush-Cheney White House led to the end of their Republican party and the creation of Trump’s MAGA Republicans. Yet people don’t talk much about the Iraq War.

But it’s wrong for all sides to bury Iraq and glibly write it off as a mistake. In the new era we live in, with anti-democratic authoritarians and outright dictators enjoying a resurgence, a full understanding of what happened in Iraq is necessary if democratic societies — including the United States — are going to be able to halt their forward march.

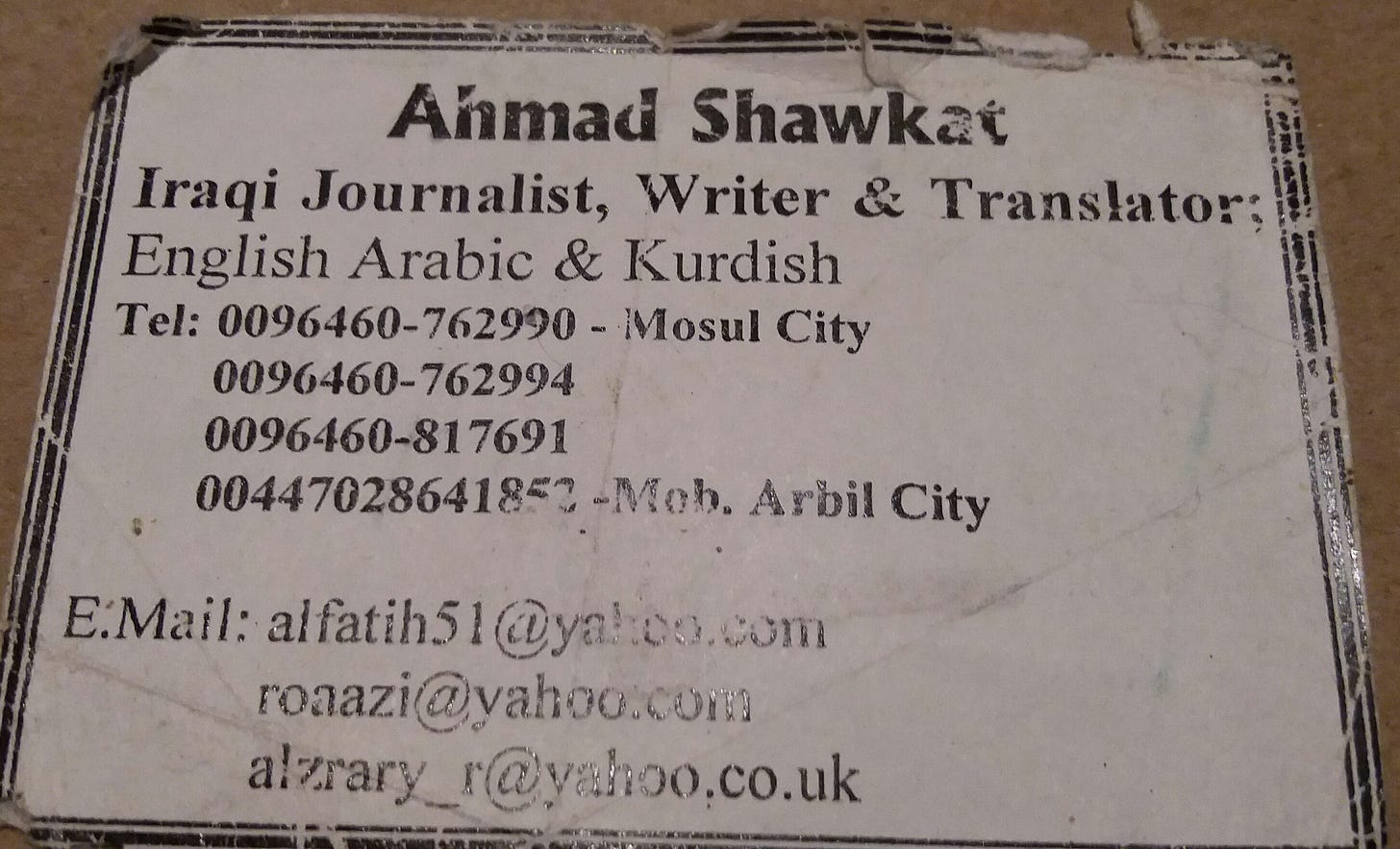

I covered the Iraq War as an unembedded reporter based in Northern Iraq/Kurdistan. My translator was Ahmad Shawkat, a political dissident who had survived imprisonment by Saddam Hussein’s regime. He embraced the war and the possibilities it brought and was murdered six months later in the chaos unleashed by the Bush administration’s catastrophic lack of planning for what to do with his country.

In every nation collapsing under the weight of dictatorship or undergoing internal assault from anti-democratic forces, there are people like Ahmad, people with whom I, and probably you, share a world view along with a desire for enlightened freedom of thought and action.

I wrote a book about Ahmad, our time together, his life growing to manhood in post-colonial Iraq, and the bitter irony of his murder when the freedom he had longed for all his life finally found him. The book was a New York Times Notable Book the year it was published. Then the publisher went out of business and the book went out of print. Now it is republished by Envelope Books as The Martyrdom of Ahmad Shawkat and this is the first chapter.

As happened then, there would have to be diplomatic shadow plays at the United Nations to cover the time necessary to ship troops to the region. Emissaries from the international community’s organizations and self-appointed peacemakers from Britain’s left would go to meet Saddam Hussein and treat with him. Then, when all the troops were in place, there would be a collective inhalation of breath and silence on earth for about the space of forty-eight hours. And in that time the final, predictable actions would occur. The United States would order Saddam Hussein to get out of Iraq. The dictator would refuse.

And the Kurds would take to the mountains.

Despite the establishment of a Kurdish safe area in northern Iraq after their failed uprising at the end of the 1991 Gulf War, very few Kurds felt that they would be protected from Saddam once this conflict began in earnest.

As the deadline for the dictator to leave the country approached and the final countdown to war began, the Kurds of the northern city of Erbil loaded up their cars and headed for the mountains. Situated on the plain of the Fertile Crescent, with a division of the Iraqi Army deployed only a twenty-five-minute drive away, Erbil, with its population of more than half a million, was the most exposed large city in Kurdistan. With the expertise learned over decades of dodging Saddam and the Kurds’ own occasional bouts of infighting, the cars and ancient flatbed trucks were packed with necessary household possessions, the kids finding places to sit where they could. Then the vehicles headed up toward the mountains, suspensions strained to the breaking point, undercarriages scraping along the bottoms of the switchback mountain roads.

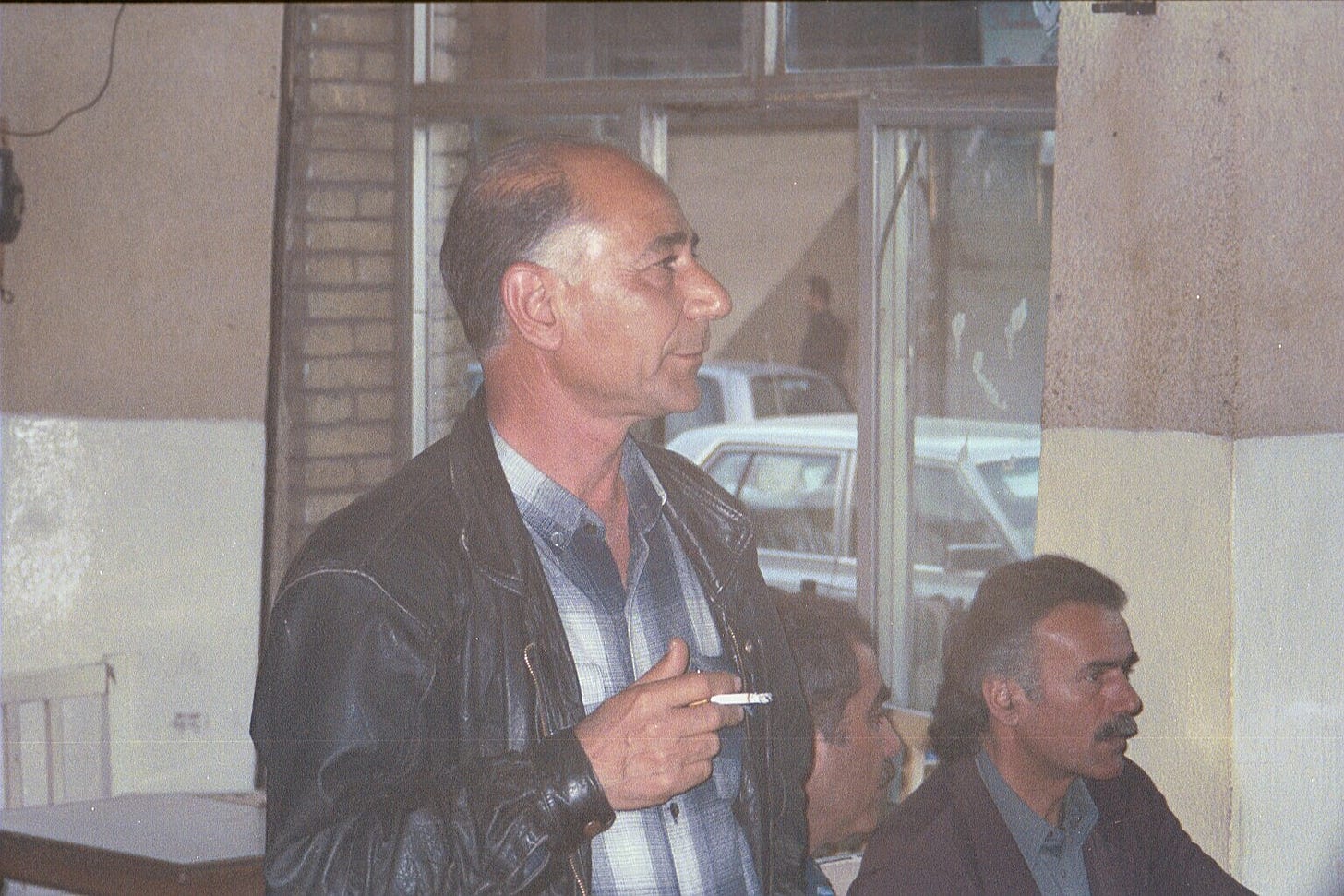

The night before the war started, Ahmad Shawkat was seated in the Erbil Tower Hotel at the foot of the city’s Citadel. Most of his neighbors had fled, but Ahmad stayed in town. Like most Erbilians who could string three sentences of English together—and he could do much better than that—Ahmad was hoping to work as a translator for one of the dozens of Western reporters who had come to the Kurdish safe area of northern Iraq to cover the war.

He had had a bit of work during the few months leading up to the start of the conflict, but nothing proved steady. Reporters come. In the middle of the night they get a phone call from their editors. Reporters go. Now it was getting late to hook up with someone. Anxiety shrouded him. At home he had a wife and six children, but he was providing nothing for them, and as war approached he saw his opportunity for work slipping away. He had spent most of the day moping about the house until Roaa, his oldest daughter still living at home, urged him to go to the Erbil Tower one more time. He dragged himself from the house and went to the hotel and counted out more of his life passing away. Sitting quietly. Waiting. Smoking. Watching but not really paying attention to a Fox News broadcast playing on an ancient large-screen TV in the lobby.

A steady rain was falling in Erbil the day before the war started. Rain on the plain meant snow in the mountains. At the Iranian border, spring blizzards blew through the mountain passes, dropping weighty, wet snow on the trickle of late-arriving jour- nalists heading down to Erbil through Iran. The border crossing at Hajj Umran is in a mountain pass almost a mile above sea level. As the road slid down from the pass, the snow turned to rain, and I could see the steady stream of heavily laden cars heading to the mountain villages or just pulling off to the side of the road, their occupants setting up camp in the mud. Men were putting up plastic sheeting for shelter, desperately grabbing at loose corners as sheets flapped in the wind. Women and girls in soggy burnt-orange and crimson dresses were down by fast- running streams drawing water for their families. Occasionally they looked up into the car headlights rolling by, dark hollows around their eyes and pinpoints of white in their pupils.

Their faces registered in my brain with the surreal clarity imparted by sleep deprivation. To get to Kurdistan before the war started I had been traveling for a day and a half without sleep. That was on top of the adrenaline-laced, sleep-deprived last few days I had spent in London getting myself ready, sweating out my Iranian visa—by then the only way into Iraq was to cross over at the Iranian border—packing, checking, and double-checking my recording equipment, and, finally, taking delivery of my body armor, which arrived just a few hours before I was due to depart on Monday, March 17. It was a good bet the war would start on Thursday. And once it started, the Iranians might also close their border with Iraq.

Tuesday night I flew hundreds of miles farther east than I needed to, to Tehran. Then, in the morning, I doubled back by air northwest to Orumiyeh, up in the Iranian mountains, then traveled by taxi due south to the border with Iraq. In Tehran, I had been kept waiting through the small hours of the morning while the local authorities fingerprinted me, a retaliatory indignity for the mass arrest of hundreds of Iranian men in Los Angeles the previous summer. Then, at the border, I was kept waiting in my car while a blizzard rolled in and one of Iran’s local tyrants decided whether to acknowledge Tehran’s authority over him. A fax from the government’s Ministry of Islamic Guidance and Culture, giving me permission to go into Iraq, was on the desk in front of him. After a few freezing hours, it became clear what was going on. A hundred-dollar bill opened the gates to Iraq for me.

The Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) had handled my travel arrangements. Over the years the KDP, one of two main political groupings in the Kurdish north of Iraq, had put together a very effective media machine, facilitating journalist access to their hemmed-in, semiautonomous entity. On the Iraq side of the border, cars were provided to get us to Erbil. I piled my gear into a Mercedes and headed down the mountain. As the car flashed past the Kurdish girls, their raven hair washed out from under their head scarves by the steady rain, the tension inside me began to ease. I’d made it. I was in. I didn’t even have to worry about finding a hotel. The KDP had booked me into a place with the magical name Dim Dim. “You will like it. It’s a five-star hotel,” their mustached representative at the border had told me. A five-star hotel sounded good, if unlikely. But at least I knew for certain I had a bed waiting. The war could begin now. All I needed to do was find a translator, though I figured that could wait until the next day. Now I needed rest.

By the time our little convoy of late arrivals got to Erbil, it was already evening. The Dim Dim was not quite as advertised, but by local standards it was quite grand. On my previous visit to Kurdistan, in the summer of 1996, the hotel I’d stayed in was so foul, I’d ended up sleeping on the roof under the stars. But the Dim Dim was reasonably well maintained. Its rooms were a decent size, and the bathrooms had sit-down toilets and a plentiful, if slow-arriving, supply of hot water.

The lobby of the Dim Dim was covered in marble and it was full of men. The lobby of the Dim Dim was always full of men: translators, drivers, bodyguards. In Kurdistan men are rarely at home. Home is a foreign, feminine country from which men flee each morning, return to briefly in the midday for a meal and a nap, and then run away from again. They return only when there is no longer an excuse to stay away. There would be plenty of translators to choose from in the morning.

In the morning I worked my way around the lobby and quickly figured out there was no one suitable. Most of the people in Erbil who spoke English reasonably well had already been hired. But I needed more than “reasonably” good translation anyway. My assignment for the public radio program Inside Out was to follow the war through an Iraqi’s eyes. I had come up with the fanciful idea of finding someone who had suffered under Saddam’s regime, documenting their liberation, then turning their experience into an hour-long program ready to air on radio within a month. All I needed to do was find a willing subject. That would be my translator’s first task. He or she would have to know Erbil very well to help me find this person. Then we could proceed to the linguistic skill department.

What I needed from my translator, aside from grammatically proficient English, was detailed accuracy. For a short daily news report, summary translations are okay. So long as the translator accurately and quickly renders the basic facts—what happened, when, how many people were killed, how many people fled— you have the information to fill up three minutes of airtime. But when a reporter tries to take people deep inside someone else’s war-torn world, to keep listeners attentive the journalist has to offer clear details of what’s being said.

For example, I interviewed a Muslim peasant woman in eastern Bosnia who was returning to her homestead five years after the conflict there ended. The last time she was in that place Serbs butchered her husband in front of her. The old woman was telling me the most intimate, heartrending details of her tragedy. A translator’s natural tendency is to mediate and retell the story in the third person: “She says the Serbs destroyed her life.” What I needed to hear was the direct, first-person story— “The Serbs came and destroyed my life”—otherwise the tape would not be usable.

Then a broadcaster needs the details. Conversation flows more freely when a reporter picks up on the detail of what’s being said. The interviewee recognizes that the journalist really cares about what he or she is saying, and is inclined to open up even more. But to get all the details the translator needs to have an impeccable sense of timing. The translator has to know when and how to stop someone in mid-flow to translate what has been said already and not cause the interviewee to lose his or her train of thought.

I also look for someone who won’t edit comments that he or she thinks reflects unfavorably on their country. In the Arab world this is a particular problem. Arabic speech is characterized by magnificent, allusive rhetoric. Expressions of criticism, anger, or hatred are never simple and direct, and they flow in torrents. If someone is angry about an American policy, the way in which that is expressed can sound offensive if translated literally, so a translator will tend to smooth the anti-Americanism out.

Then there is anti-Semitism. People in Arab countries often speak to strangers about Jews in the same way many whites spoke to strangers about blacks in pre–civil rights Mississippi. There is an implicit assumption that you, too, know they are an inferior, barely human group who really shouldn’t be sharing space on the planet with you. Most potential translators in the Arab world are aware of the sensitivities of American reporters to such blatant anti-Semitism, and many will try to tone it down. But that takes a reporter further from the truth of what an interviewee actually believes. Usually, at some point in my reporting trips to the Middle East the subject of the Zionist entity—many Muslims will not say the name Israel, since that would imply that the state has a right to exist—comes up, and I will have to tell my translator to translate fully what is being said. I have to assure the translator that, as a Jew, hearing people express their anti-Semitism in an unguarded way is very useful.

Bigotry is a subset of the category stupidity. It helps me gauge someone’s intelligence.

I hear a lot of this hatred. Most of the ordinary people I talk to in the streets do not recognize me as a Jew. My looks don’t conform to their stereotype. I don’t have a beard nor do I wear a yarmulke. My name, which would cue most Americans or Europeans to the fact that I am Jewish, doesn’t register that way either. The Arabic custom in naming is simply to give a child a single name. Then add on the name of the father, possibly grandfather, and perhaps an indication of tribe or village. So when I introduce myself as Michael Goldfarb, people in the Arab street hear my name as Michael. I am called, politely, Mr. Michael instead of Mr. Goldfarb. Michael has a generic European sound to it. My translator in Jordan explained that most people in the Arab street think a Jewish name sounds like David Ben-Gurion or Binyamin Netanyahu or Ariel Sharon— Israeli names.

I have still more requirements of a translator. I need someone at ease with all strata of his society. This is not always possible, because in many places the person who speaks English to the standard I require comes from the well-educated upper classes and may not have a natural ability to talk to peasants or the working classes, the people who usually suffer most when the world is in upheaval.

Beyond linguistic accuracy I need a good companion. We’re going to be together in a car for hours every day for weeks at a time traveling to wherever the news is. You need to be able to joke, talk about your families, and discuss politics without getting into arguments. I also need to be certain that the translator has a good work ethic. The harsh necessity of deadline overrides everything, even having lunch.

Finally, a translator needs courage, because in a conflict reporters have to get as close as possible to the fighting. We are required to see as much of it as we can ourselves, to talk to combatants and civilians on the front line, to be the firsthand source of information. If your translator isn’t willing to go to the closest vantage point, you won’t get the story.

It is almost impossible to find someone who meets all these criteria. It’s very hard to meet someone who fits most of them. It is often a matter of luck whether a reporter scores a good one.

But when a reporter finds a good translator, it is a beautiful thing. You can feel the metaphorical walls separating reporter from interviewee being broken down. A good translator bridges two separate realities in the most extreme of circumstances. Sometimes you can actually see an interviewee’s pupils widen in surprise that a foreigner seems to understand their culture, their particular circumstances. Sometimes a little black humor of mine, accurately translated, brings out a smile. From that smile, you are invited to probe deeper. The only way these moments can happen is because your translator is giving you a quick, accurate translation and sending back your English with equal speed, and has established rapport and trust with the interviewee.

The young men filling the lobby of the Dim Dim were doing what young men throughout the Muslim Middle East do: sitting, talking, smoking, and drinking tea. I worked my away around the few still available for hire. They spoke English with varying degrees of precision. None met my minimum standard. I visited a couple of other hotels around the city, but the situation was the same.

Now I was getting a little nervous. I still hadn’t found anyone suitable, and it seemed likely the war would begin sometime in the night. As evening brought the conflict even closer, I decided to visit the BBC office at the Erbil Tower Hotel to see if they had the name of someone I might hire. The Erbil Tower had been turned into a fortress with a perimeter of roadblocks circling it. A couple of burly Kurds with Kalashnikovs manned checkpoints. On one of the upper floors the windows were filled with sandbags. An observer would have thought that an important Kurdish politician was headquartered there. But it was just Fox News’ team taking no chances should Saddam single it out for attack.

The paramilitary presence kept people away. The lobby of the place was nowhere near as full as at the Dim Dim. The half-dozen or so well-fed men who were hanging around watching Fox on a large-screen TV looked like bodyguards rather than degree holders in English literature. At the front desk I asked for the BBC office, and a few minutes later a young Kurdish woman came downstairs. I introduced myself and explained I was looking for a translator. She pointed to a small, quiet, middle-aged man I hadn’t seen in this lobby full of bruisers. “He is a very good man.” From the way she said good I couldn’t tell if she meant “good for the job” or the deeper sense of good as in a morally correct person, reliable in a pinch. “He is the father of my friend,” she added, which made me think it was probably the latter.

She took me over. He got up and with exaggerated courtesy shook my hand and made a little bow, as if we were meeting at an academic conference. He introduced himself: “Ahmad Shawkat.” I told him my name, and we sat down. There was a little awkward silence. A bit of sizing-up began. He was a slight fellow, thinning hair going gray, and did not have a mustache, which in this part of the world was most unusual. His voice when answering simple questions about his translating experience was very quiet—not halting, but not confident either. My initial impression was this just would not work. Ahmad seemed a bit shy; more important, he was too old. At first glance he looked to be in his late fifties, maybe even sixty. Age mattered to me. If we came under fire and needed to run or were among a crowd of people that turned into a mob, I didn’t want to worry that my translator was physically incapable of running away with me or, worse yet, was going to have a heart attack when the pressure was on. The other thing about hiring an older person is what any director of human resources will say: people get set in their ways and are very difficult to train when they get past a certain age. Then there was a corollary of the Groucho Marx axiom about not joining clubs that will admit you: This guy was willing to work with me, but if he was any good, why was he still available?

In the Middle East, good manners require that two men discussing business go through a period of small talk before getting down to the matter at hand. I was in a hurry, however, and went straight to the formalities: Had he worked for Western journalists? How well did he know the country? The local political leadership? Did he speak Arabic as well as Kurdish? He gave brief, satisfactory answers. Then he volunteered the fact that he wasn’t actually from Erbil. He was from Mosul, over in Saddam regime territory. I asked if he was Kurdish. “Of course,” he replied. “Mosul is a very mixed city.” I asked him how old he was. There was a pause while he calculated what the boundaries of plausibility were. I know because, being past fifty myself, I’ve taken that pause when asked the same question. “Forty-five” was his answer. A wholly implausible figure. Before I could say anything, Ahmad changed the subject.

“Do you know William Faulkner?”

“Well, not personally. But of course I know his writing.”

“I love Faulkner. The Compson family. I love The Sound and the Fury. I have read it many times. I love it, how he writes from inside the mind of the boy who is mentally ill.”I nodded. “Benjy. One of my favorite sentences in the English language is ‘Firelight was still the same bright shape of sleep.’ ”

“Yes. He is a very Arab writer.”

“I’m not so sure about that.”

“No, really. We like him very much.”Then he added, “I like the sentence ‘They endured.’ ”

Now, this was not a conversation I expected to be having on the eve of war in Iraq. But I hadn’t discussed or thought about Faulkner in a long time and I went along for the ride. We spent a few minutes trading Faulkner trivia: two middle-aged men competing like the smartest kids in the class about who knew more about a favorite author. Then he said,

“I can see you are well cultured.”

It was an unusual phrase, one that required a bit of consideration; it seemed that meant I had met his requirements. He asked,

“You understand that you cannot write about Iraq without knowing about the people and the history also?”

I nodded.

“I know these things very well. I will work with you and tell you about them. But you must agree that we stay together until the war is over.”

It was an extraordinary demand. Still, it’s not every day you meet someone in a war zone who speaks English as idiosyncratically as Faulkner wrote it. Ahmad seemed unlikely to meet my first linguistic criterion for a translator: simple clarity. But on the other hand, he would certainly meet my last: on a tedious three-hour drive through the mountains we probably wouldn’t lack for conversation. So I found myself agreeing to his demand that we stick together, and decided to hire him.

Business finished, I said I was going back to the Dim Dim. I was tired and wanted to rest. But Ahmad decided for us that my education would begin immediately. He dragged me up the steep slope leading to Erbil’s Citadel. By going up the hill we were going back to the beginning of civilization.

“They say this is the oldest continuously inhabited settlement on the face of the Earth,” Ahmad explained. “Since 5000 B.C., maybe 6000 B.C., people gathered in this place. The Assyrian empire, the first empire on earth, was founded not far from here. But even before that there was a settlement here.” Each millennium had added layers to the Citadel. The walls now towered nearly 105 feet above the town.

At the top of the slope, near the gate into the Citadel, a bonfire was burning. It was the start of Narooz, a festival that goes back to the founding of the Zoroastrian religion sometime in the first millenium before Christ and, like the origins of the Citadel itself, probably beyond that in time. Fire is critical to worship among the Zoroastrians. Natural fire, not the kind made by striking flints to get a spark, is a unique feature of this part of the world. Not far from Erbil, fire comes up out of the ground, great pools of it.

Ahmad began a little lecture.

“Oil seeps out of the ground in this area. Sometimes it catches fire. There are many fire- worshipping cults. There is a place near Kirkuk called Baba Gurgur. . . . In ancient times women went there who could not have children. They bathed in the oil and became pregnant.”

Fire and oil, oil and fire: the foundation of the world of men. As it is now, was then, and evermore shall be. Normally, on the eve of Narooz, Erbil would have been full of people dancing around bonfires, but on this night, with war soon to begin, only a small group of fellows was hanging around this solitary fire at the entrance to the Citadel. A crew from Syrian television drove up, and the Kurds began a desultory performance of a tradi- tional dance for the camera. I recorded a bit of the singing. We watched for a while longer and then walked through the darkened complex.

Despite its grand name and the pride with which Erbilians speak about it, the Citadel is a wreck. Layer upon layer of human civilization has risen for eight thousand years to a topographical high point, but inside the walls development seems to have stopped a couple of millennia past. The interior was a mud-hut peasant village, the houses crumbling away, its higgledy- piggledy pathways unpaved. A single lightbulb illuminated a front room somewhere off to our left. It was the only sign of human life in the little village inside the wall. The residents had fled to the mountains, but their animals—dogs, cats, sheep, and chickens—wandered underfoot as we walked carefully through the darkness, talking about this and that.

Although the language Ahmad and I used was formal, there was an odd familiarity in our conversation. A couple of bookish men talking a bit about authors and local history, the subjects intellectuals all over the world use to feel out new acquain- tances. But both of us were so advanced into middle age that we didn’t express any surprise at having this conversation while wandering through an empty city on the eve of a war. It was a simple pleasure not worth remarking on. We moved from small talk to getting-to-know-you talk. We spoke of children. He asked me if I had any. “No.” It’s a painful subject for me, so I quickly shifted the question back to him. Ahmad was typically fecund in this area: he had eight; six children were living with him in a house not far from the Citadel in an “old quarter, very intellectual.” He had two married daughters still in Mosul.

“Why did you leave Mosul?” I asked. “Politics?”

“Yes. Things I wrote. I have been arrested many times.”“Tortured?”

“Of course. When I released, I came here.”

As we wandered through the ancient walls we later learned that American jets were striking “a target of opportunity” in Baghdad. This attempt to take out Saddam on March 19, 2003, would fail, and from that moment on a full-scale invasion was inevitable. We walked down a steep flight of stairs on the other side of the Citadel across from the shuttered-up bazaar. The empty city had lost its background din; a Kalashnikov fired for fun several miles away could be heard as clearly as if it had been fired around the corner. The thunking of an old taxi’s engine caught our ears long before we saw it. We hailed the cab and jumped in. Erbil’s main streets are laid out in circles around the Citadel. We swung around the great mound, and just by a dilapidated office building Ahmad had the cab stop. He pointed at the building.

“Can you remember this place?”

“Yes.”

“This is my street,” he said, pointing down a narrow, darkened road. “If anything happens you can come to my house and you will be safe.”

It was a polite thing to say, but if Saddam decided to launch a chemical or biological attack on Erbil, there really wasn’t much we would be able to do about it. As Ahmad was getting out of the car, I realized I didn’t have his phone number. I grabbed his arm and asked him for it. He took out his business card and handed it to me. There were three e-mail addresses but no phone number. I looked at him quizzically.

“These first two e-mail addresses belong to my daughter. This one is mine,” he explained.

“Al-Fatih 51” I read out loud.

“Al-Fatih means ‘the leader,’ ” he said. “It was my name in underground movement.”

Interesting, I thought to myself, then I asked him where his phone number was.

He confessed he didn’t have one. He wrote down a number and explained it was not his own phone. It was the number of his neighbor, and if I needed him for anything, anything at all, I was to call there and his neighbor would find him. If I had known that he didn’t have a phone, I might not have hired him, but now it was too late. Besides, I had enjoyed our conversation. I already liked the guy.

He got out and the cab took me on to the Dim Dim. I kept thinking about something he said as we walked through the Citadel.

“When the U.S. gets rid of this bloody Saddam, I am going back to Mosul.”

Mosul was just sixty miles away. There were two rivers, one ridge, and a single division of the Iraqi Army between Ahmad and home. It didn’t seem like an impossible dream. I thought it might be worth following him there.