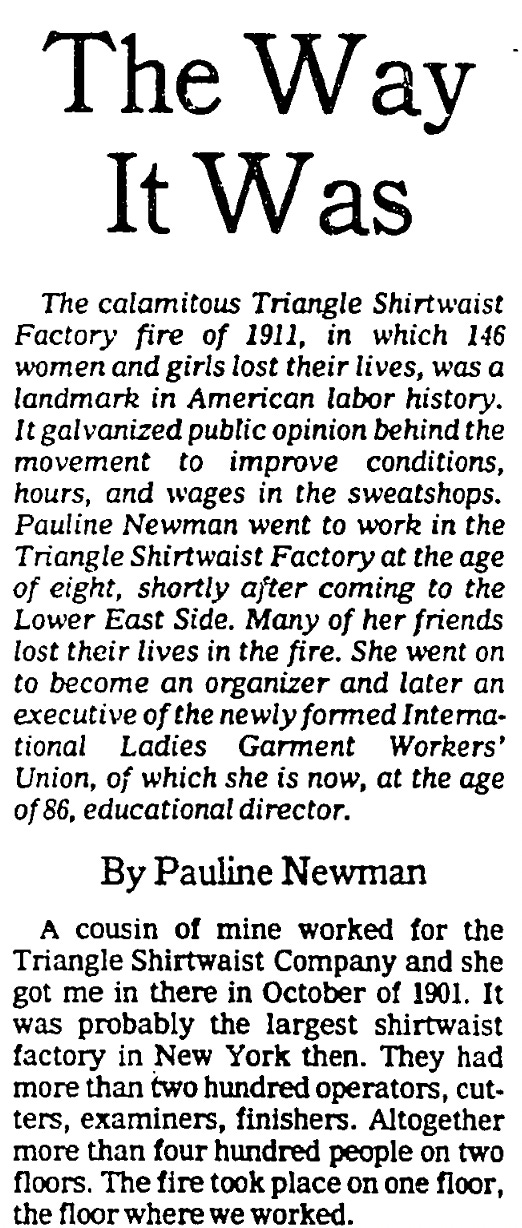

Through the miracle of the internet and the New York Times’ willingness to put its archives online, every Labor Day I re-read this article, published exactly 44 years ago today:

Eight-year old Pauline Newman earned $1.50 a week for what were frequently more than 12 hour days and, in busy season, seven days a week. No overtime. A buck fifty.

The whole article details how she avoided the fate of the 146 women who perished. It’s the conclusion that hit me hardest:

I can remember where I was and what I was doing on the day this was published: staring at the ceiling in my apartment at 119 west 15th Street in New York considering my options. I was collecting unemployment and about to turn 30 in three weeks, my self-imposed deadline for making it as an actor. What qualified as “making it” had changed over the years from regular work on Broadway and films, to steady jobbing work as a lead player in regional theatre, to just paid work eight months a year doing anything. Not even that was likely. It was time to leave New York and remake myself. But where and how? No idea. I was sliding towards depression from my own indecision and self-pity, enduring Hamlet’s dilemma without the pleasure of actually playing the part.

Reading Pauline Newman’s op-ed put an end to this foolishness. What was a little personal failure compared to what she, and my grandparents and great-grandparents endured in the years they lived on the Lower East Side?

We had learned about the Triangle fire in Hebrew school. Most of the victims were Jewish immigrants like our grand-parents and in the early 60s when I was studying for Bar Mitzvah the distance between the Jewish community and labor unions was not as great as it has become. Many of my Hebrew school classmates at Beth David synagogue in the Wynnefield section of Philadelphia went to Samuel Gompers Elementary school. Gompers, a Jewish immigrant from Amsterdam via Whitechapel in London’s East End, had founded the American Federation of Labor. Family legend said my great-grandfather had worked with Gompers as an organizer in the cigar-makers union.

Newman’s essay was personal. Today, when you read something interesting in the paper, you post a link to it in social media but back then I told no one about this essay. It was a personal message, like a scolding from my Uncle Morris, “You think, you’ve got it tough? Boo-hoo. This is what tough times and struggle really are.”

Three months later I had moved to Washington and begun a new life at the very bottom of the journalism ladder, as the oldest copy-aide at the Washington Post.

There are many reasons I have not forgotten this op-ed — particularly the concluding paragraph reminding people in 1980 that their leisure time was purchased at a high price — but the main reason is because it motivated an unemployed, failing actor to stop whining and start marching down the path he was supposed to be on.

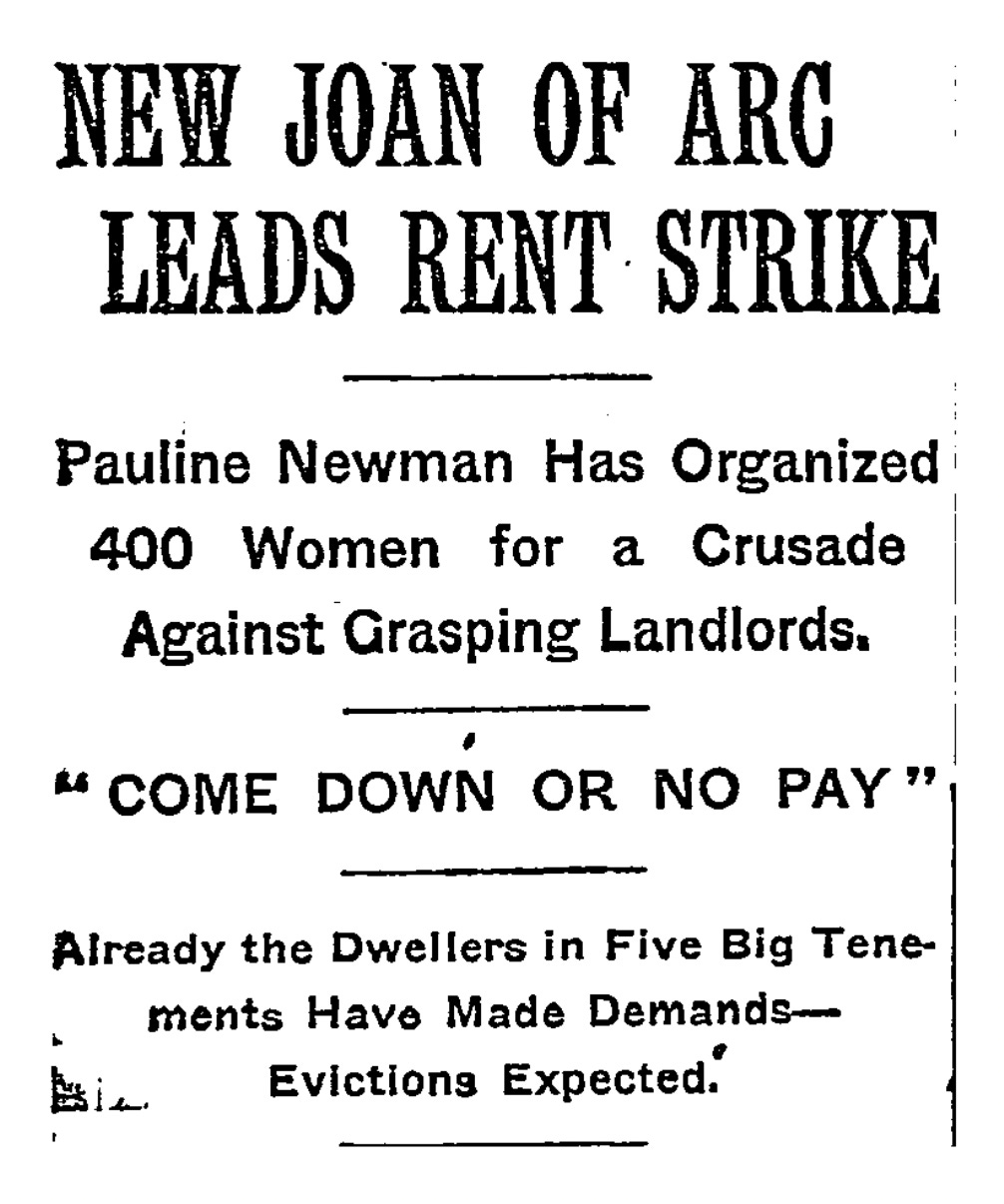

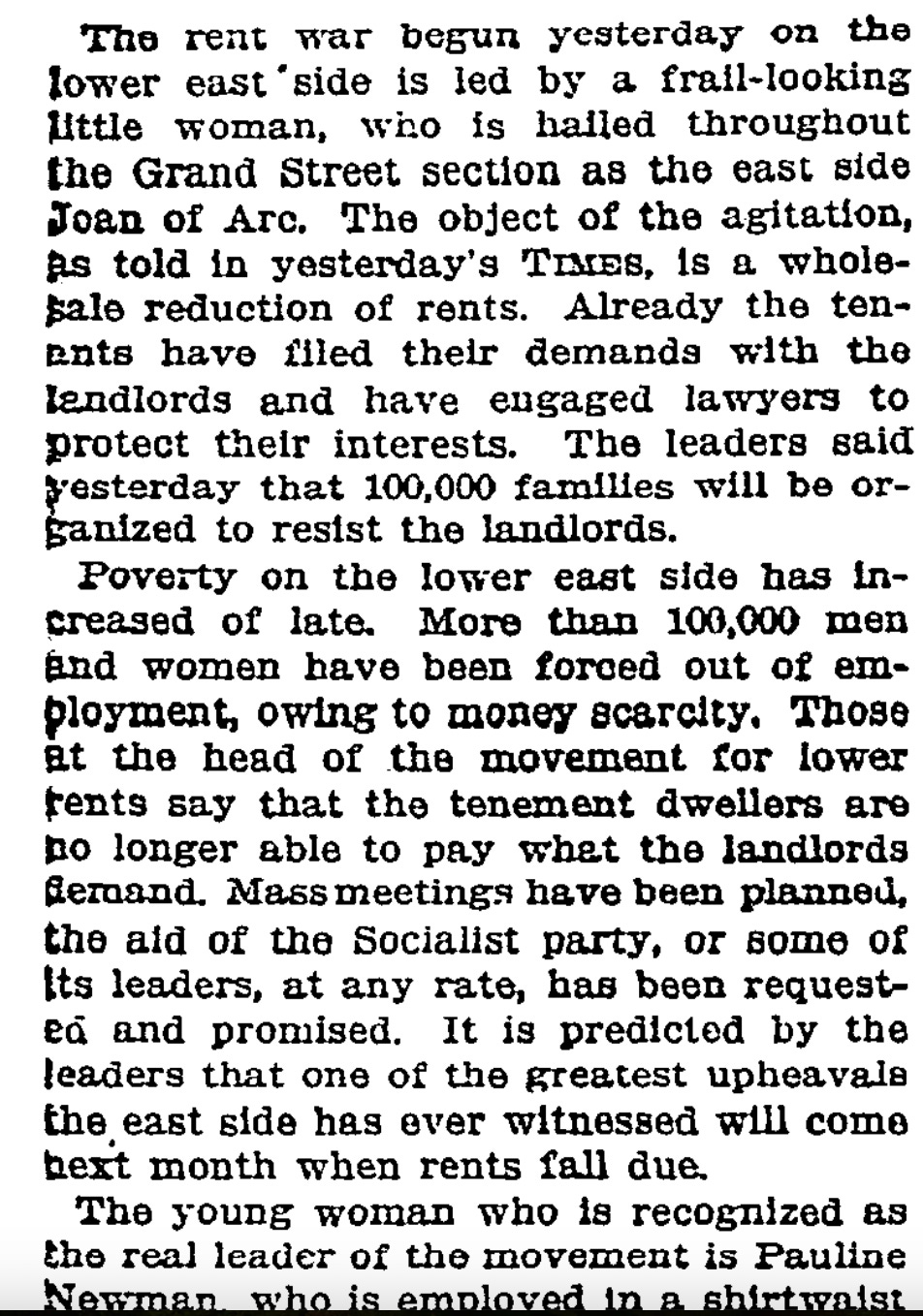

Interestingly the op-ed was not Pauline Newman’s first mention in the Times. That came on December 27, 1907.

Newman was not quite twenty when she organized the rent strike. The article lists half a dozen properties on the Lower East Side where rents are being withheld. Two are on Cherry Street where my grandfather grew up. He would have been eleven at the time. I wonder if he ever saw her?

Pauline Newman died in 1986 at the age of 98. For me, truly, her memory is a blessing.

And here’s something completely different from the usual FRDH subjects of war and politics for this end of summer weekend: a conversation about Paris.