I awoke to the ancient, comforting sound of a faraway freight train blowing its horn and the rumble of boxcars behind it. Deep country Georgia. Election Autumn 2024

I am in Sumter county, location of Plains, whose most famous resident, 100 years old, lays dying not far from where I am writing.

Whether he makes it to Election Day or not, his passing will mark the last living connection to a different age in American public life: a time when a farmer from the smallest of towns could make it to the White House and bring with him a genuine sense of small town decency.

I arrived in Plains via back roads, in some cases just packed down red Georgia dirt. For miles around, the autumn snow of cotton was in various stages of being picked. It’s not done by hand anymore — enormous combines chop it and then roll massive bales to be taken to be ginned. I could not begin to imagine a person from this life ever making it to the White House again. Urban skills and big city money are the prerequisite for the presidency these days. Even Bill Clinton, who grew up in Arkansas didn’t come from the farm or a one-track town like Plains.

The Carter story is well-known and his obituaries have been ready since it was announced he was receiving home hospice care for brain cancer 19 months ago. Some outlets have grown tired of waiting for the actual event and have begun publishing the obits as appreciations. This by Spalding Professor of History James Cobb of the University of Georgia, is an excellent, warts and all appreciation of how in his first political steps, to win Georgia’s governorship, Carter did what was necessary in a state where the white crossover from Democrat to Republican in the wake of Lyndon Johnson’s Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts was just getting underway.

That was 1970, By the time he ran for President, just six years later, he had shed what Cobb calls moderately segregationist views — views that perhaps he made public for the pragmatic necessity of getting elected — and was a mainstream Democrat who held the magic combination for the party after the tumult of the Sixties: he was from the South, which was slipping away, and he had a military background.

He also wore his piety on his sleeve. He knew right from wrong.

Gerald Ford having pardoned Richard Nixon was never going to be able to overcome that in a country where a majority of the electorate thought the President, at least, should have a moral compass.

Historians judge Carter’s presidency as a mixed bag but generally not a very good one. I won’t go into a list of the successes and failures. When he finally departs, the obits will deliver the chapter and verse. I want to talk about the infamous “malaise” speech in which the word “malaise” does not appear.

The speech, delivered, on July 15th, 1979, contains words that speak to the condition of American society today. The theme was energy self-sufficiency. Oil prices had spiked again. The country’s economy had just got past the inflation of the 1973 Oil Shock caused by the Yom Kippur War and now, because of the Iranian Revolution prices, prices were spiking again.

But Carter moved past the immediate problem to talk about something deeper in that was ailing the country — besides gas prices and long waits at filling stations to get fuel. In his view:

It is a crisis of confidence.

It is a crisis that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our nation.

The erosion of our confidence in the future is threatening to destroy the social and the political fabric of America.

The confidence that we have always had as a people is not simply some romantic dream or a proverb in a dusty book that we read just on the Fourth of July. It is the idea which founded our nation and has guided our development as a people. Confidence in the future has supported everything else -- public institutions and private enterprise, our own families, and the very Constitution of the United States. Confidence has defined our course and has served as a link between generations. We’ve always believed in something called progress. We’ve always had a faith that the days of our children would be better than our own.

Our people are losing that faith, not only in government itself but in the ability as citizens to serve as the ultimate rulers and shapers of our democracy. As a people we know our past and we are proud of it. Our progress has been part of the living history of America, even the world. We always believed that we were part of a great movement of humanity itself called democracy, involved in the search for freedom; and that belief has always strengthened us in our purpose. But just as we are losing our confidence in the future, we are also beginning to close the door on our past.

As you know, there is a growing disrespect for government and for churches and for schools, the news media, and other institutions. This is not a message of happiness or reassurance, but it is the truth and it is a warning.

These changes did not happen overnight. They’ve come upon us gradually over the last generation, years that were filled with shocks and tragedy.

Then, Carter referred to the recent past

We were sure that ours was a nation of the ballot, not the bullet, until the murders of John Kennedy and Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. We were taught that our armies were always invincible and our causes were always just, only to suffer the agony of Vietnam. We respected the Presidency as a place of honor until the shock of Watergate.

Thank goodness we no longer live in a society where progressive leaders are murdered, but the rest of what he describes is close to our situation today. You can substitute Afghanistan and Iraq for Vietnam to get the sense that American military invincibility is once again in doubt. As for the last sentence, you could substitute Donald Trump for Watergate easily enough.

If you weren’t alive then — and even if you were — it is easy to forget now what the Democratic party that nominated Jimmy Carter and got him to the White House was like. Its energy came from a still comparatively young generation, chastened by the hammering it had taken in 1972 when that generation — my generation — had managed to nominate George McGovern whose anti-Vietnam War stance was ideologically pure but anathema still to the majority of voters. Before that this generation of activists had worked against Hubert Humphrey in 1968 because he would not step away completely from Johnson’s policies on the war.

I’m not sure how many of us really embraced Carter. Chastened enough to vote for him, arrogant enough in our youth to not really trust his piety and decency.

In any case, the speech was savaged. Politicians learned the lesson. No American President since has ever dared speak honestly to the nation when it was going through difficult times economically or socially.

As he wound up the speech he kept emphasizing the word faith.

We simply must have faith in each other, faith in our ability to govern ourselves, and faith in the future of this nation. Restoring that faith and that confidence to America is now the most important task we face. It is a true challenge of this generation of Americans.

And he closed:

Working together with our common faith we cannot fail.

It is a measure of how far from decency and the meaning of faith America has fallen that pictures of “Evangelical” pastors laying hands on Donald Trump is now a trope of his campaigning.

It is doubtful that Carter could ever have beaten Ronald Reagan for a second term. All occasions informed against him: The Iran hostage crisis, inflation from the second oil shock, and the lukewarm approval of his own party doomed him to defeat.

And with that defeat, basic decency slowly evaporated. It is ironic that at the same time he was President another Georgia politician was giving his own speeches to young Republicans in that state — as he tried for a third time to get elected to Congress — charting the new course:

I think that one of the great problems we have in the Republican Party is that we don't encourage you to be nasty. We encourage you to be neat, obedient, and loyal and faithful and all those Boy Scout words, which would be great around the camp fire, but are lousy in politics.

…

You're fighting a war. It is a war for power.

War — something Gingrich never experienced, he dodged the draft — is not a place where decency will help you survive. Gingrich’s inversion of Clausewitz, that politics is war by other means, has been the driving force in Republican politicians’ retreat from decency and made the party ripe for Trump and the MAGA movement.

About Carter’s genuine decency much has now been written. His, now 44 year long post-presidency has provided many examples of his good works. But I do have a personal one. I left my native New York for London in the autumn of 1985. There were many reasons for it but I was at an economic low-ebb, living among the ruins in Alphabet City on 7th Street between Avenues C & D. Over nearly two decades vast swathes of the city were intentionally left to rot and burn. It is no exaggeration to say that many of the blocks around my apartment looked as bombed out as any German city circa spring 1945.

One summer afternoon I was reading/dozing in my flat when I heard the high-pitched whine of drilling through lumber and plasterboard, followed by the incessant thumping of hammers. Jimmy Carter was a block down working on an abandoned tenement, a Habitats for Humanity project was underway. So one of my memories of departure from my native country is the sound of a decent man who once had been President living and acting on his beliefs and faith, rescuing an abandoned building to house people on low income.

So now it’s 2024. All that I was unable to do professionally in America I have been able to do since leaving. I’m back in Georgia covering yet another election in which Donald Trump has a good shot at the White House, a reminder of America’s callamitous decline since Carter’s presidency. I felt I should at least visit Plains as a sign of respect.

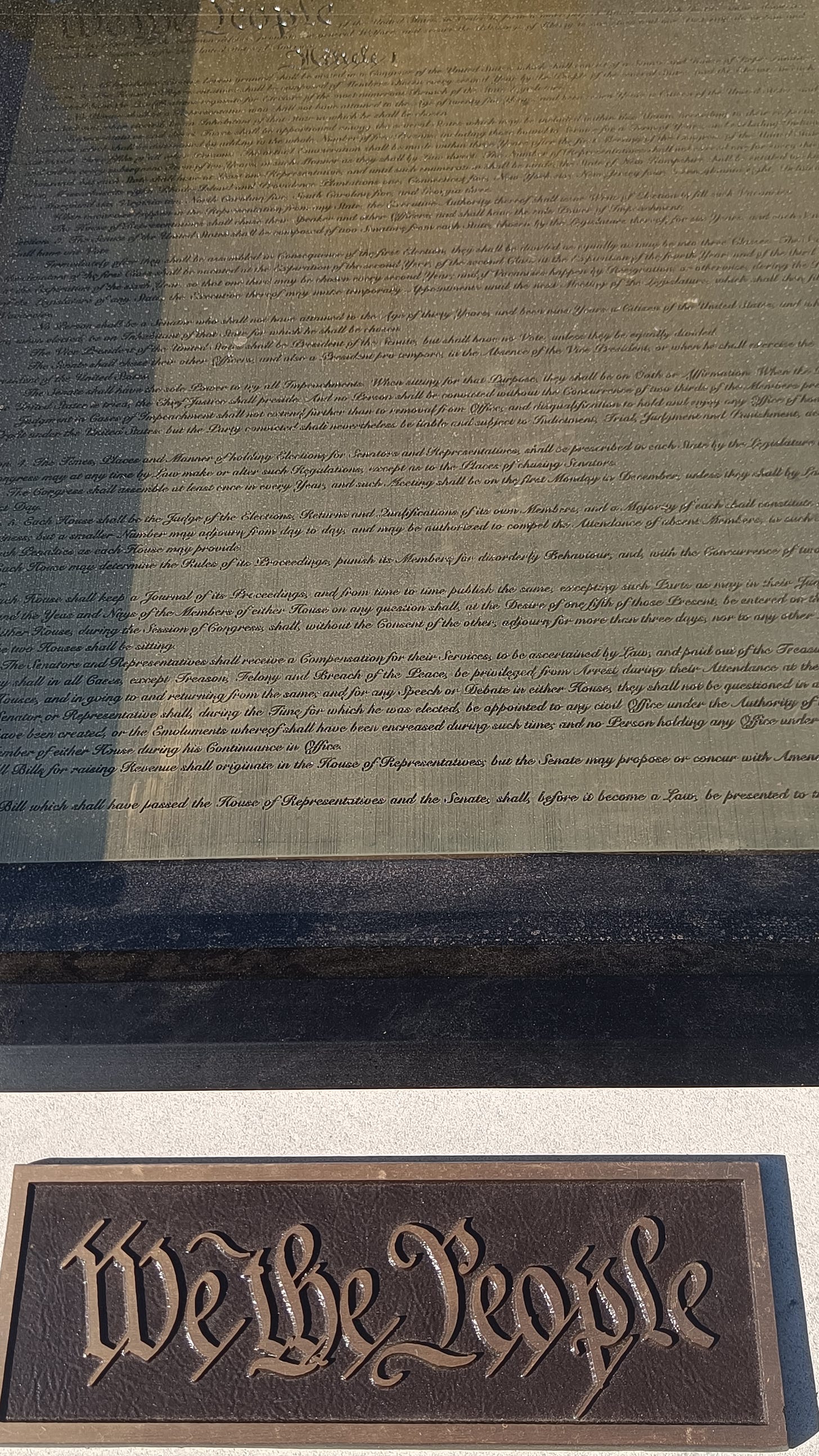

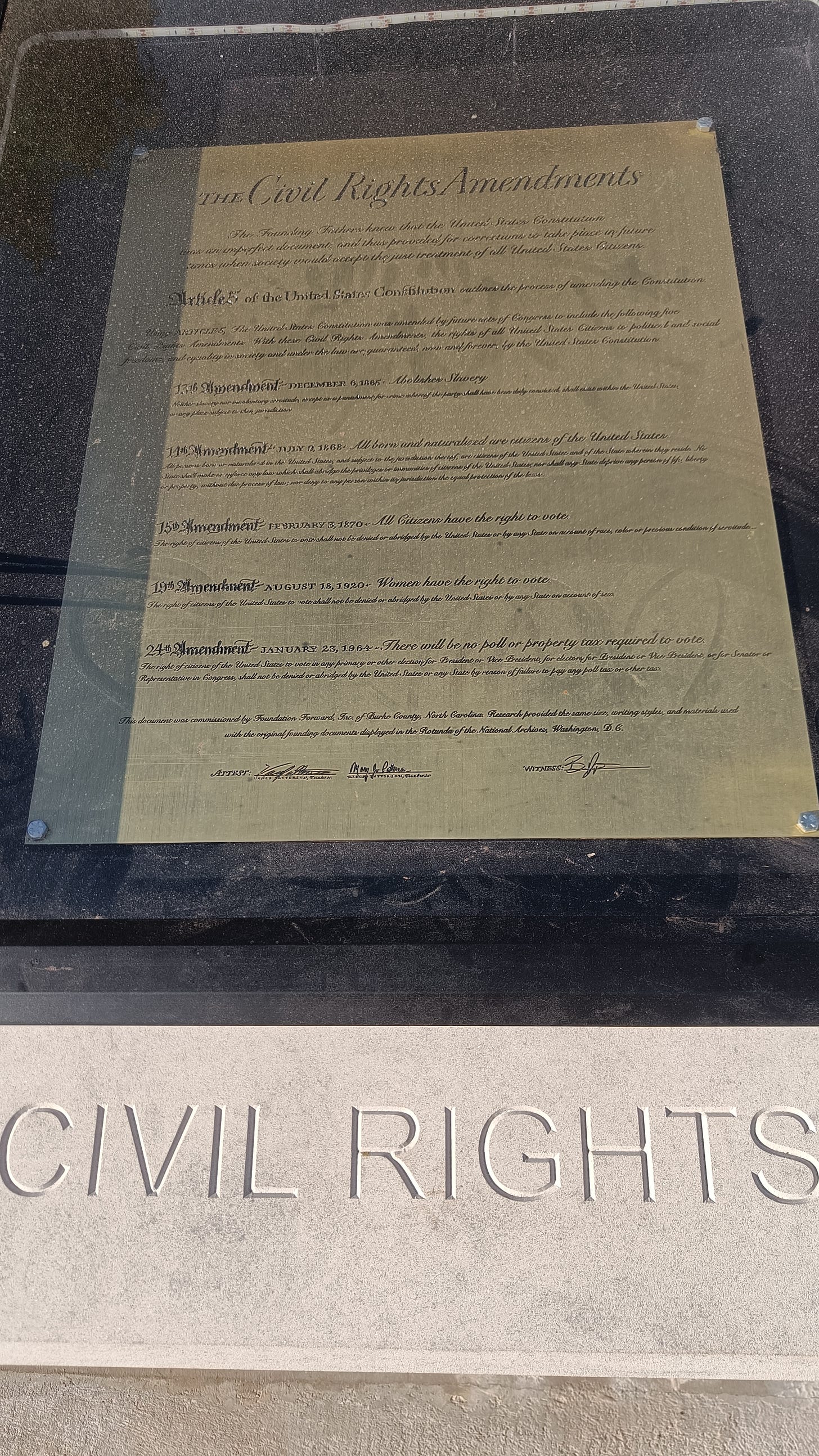

Across from the shops in the picture at the top of this essay is a series of concrete display cases with copies of the key texts of the nation

It is simple and inspiring, but I would be dishonest if I didn’t note this sign, one of many, along Main Street, a few hundred yards from his sick bed.

A prophet is not without honour, but in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house.

Mark, Chapter 6, verse 4

This is the fifth of my dispatches from Georgia and North Carolina. Both states are critical to Donald Trump and Kamala Harris’s hopes of winning the election. And both are competitive according to opinion polls but, as you can tell, I prefer to gather my own facts.

I plan to stay here through the counting of the vote, which promises to be fraught, particularly in Georgia but I need your help to do it. Here’s how:

OR TAKE OUT A PAID SUBSCRIPTION HERE

And read History of a Calamity, How America Got from Victory in World War 2 to Donald Trump and a State of Cold Civil War

Excellent piece. Captures the decency of Carter the man and how it made him fatally weak as a politician in an increasingly indecent arena

This is a great piece of reflective reporting. Remember Jimmy and Roslyn fondly as true blue. Your dissection of his speech in mid-1979 is a true reminder of how far we have drifted. We have yet to resolve the same issue of malaise, but now it is heavily laced with the acid poison of hate.

Let us all hope and pray that we can find this country led forward with minds both sane and kind.