BIBLE STUDY FOR ATHEISTS: HISTORY REPEATING

How the Story of the Split of the Tribes of Israel Still Shapes Jewish Life

Of the many foolish things said about the terrible war between Israel and Hamas that has reduced much of Gaza to rubble, cost 26,000 Palestinians their lives and has yet to lead to the return of the Israeli hostages held there by Hamas, the most foolish is the idea that Jews are settler colonialists. We aren’t. We really have a history in the land going back millennia. The historical record and the Bible say so, as well as the fact that there is one quality among all others that defined us as a people then and now:

We quarrel.

Jews argue with each other—all of the time—and I regard this as partial proof of the Bible. The essence of the ancient Hebrews described in the book: “stiff-necked” and quarrelsome seems to fit my people even in the present day. For years I’ve wondered about a central event of our ancient history that defined the “one people divided” state of Jewish affairs: the split of the tribes of Israel into two kingdoms after the death of King Solomon.

The northern Kingdom of Israel, composed of ten of the twelve tribes descended from Jacob, was centered in Samaria, with its capital Shechem near modern day Nablus in the heart of the West Bank. The smaller southern Kingdom of Judah clustered around the hilltop fortress of Jerusalem and the town of Hebron, 17 miles further south.

What caused this split? Was it some major theological rift or a political/ideological shift?

The story is briefly told in the Book of Kings, but is there more to it and how much of this part of the Bible is based in fact? When it comes to the two kingdoms, there is no doubt about the split. The historical record is written on monuments and clay tablets left behind by the Assyrian and Babylonian empires which show references to the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel and the murder of Zedekiah, King of Judah.

It’s hard to find objective historical studies about the people who wrote and about whom the Old Testament is written. Too much violent history gets in the way and that off-shoot of Judaism, Christianity, has its own religio-political agenda in framing the facts.

It wasn’t til the 17th century that philosopher Baruch Spinoza initiated the era of modern biblical studies. Spinoza’s key insight was that the Bible we know could not be divinely inspired because it was the work of many different translators over the millennia working on different texts in different languages. He used his knowledge of Hebrew and classical languages to set about trying to find clarity and in so doing made comparative philology the key to understanding the book.

There has been a similar clouding of understanding the past because of theological-political agendas in the era of modern archaeology. Digging up the biblical lands has become a way to assert claims to the disputed territories of Israel and Palestine.

But there is an excellent book called, The Bible Unearthed, by Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, archaeology professors at Tel Aviv University and the University of Massachussetts respectively, which looks at the veracity of the Book of Kings and proposes an interesting theory about the origins of Jewish quarrels.

The split of the 12 tribes of Israel into two kingdoms, one of the most wrenching events in Jewish history, is dealt with in the Bible in the First Book of Kings, Chapter 12.

After the death of King Solomon, of the tribe of Judah, his son Rehoboam gathered all the tribes to be acknowledged as their king. But towards the end of King Solomon’s reign there were already problems growing among his many off-spring and a prophecy had been uttered that the tribes would split up. This was punishment for Solomon taking foreign wives and letting them worship their own gods.

“Thou Shalt Have No Other Gods Before Me,” First Commandment.

The prophecy comes true. The tribal leaders ask Rehoboam to reduce their taxes, “make our yoke lighter.” The elders counsel Rehoboam to do as asked, but he doesn’t listen to them. Instead he takes advice from friends his own age and tells the leaders of the ten tribes:

“My father made your yoke heavy, and I will add to your yoke: my father also chastised you with whips, but I will chastise you with scorpions!” First Kings, chapter 12, verse 14.

The leaders respond angrily,

“So when all Israel saw that the king hearkened not unto them, the people answered the king, saying, What portion have we in David? neither have we inheritance in the son of Jesse: to your tents, O Israel: now see to thine own house, David. So Israel departed unto their tents.” First Kings, chapter 12, verse 16

Finkelstein and Asher line up the archaeological evidence, their own and others, to show there really was a split in this group of people called Israel which began sometime in the middle of the tenth century BCE.

And it does get a little confusing what “Israel” refers to at this moment.

Back story: In Genesis, Jacob, grandson of the founder of the faith, Abraham, wrestles all night with an Angel—call it a draw. In the morning the Angel tells him, henceforth you will no longer be called Jacob but Israel. “Isra,” in ancient Hebrew means struggle or fight and “El” is a word for God. At Hebrew school 60 years ago I was taught that Israel means struggles with God. (I clearly took this myth too seriously because I have struggled with the idea of God ever since.)

It also is a description of many interactions described in the Hebrew Bible with people, struggling and arguing with the single deity who has chosen them above all others as his “people.” The current view is that understanding of “isra-el” should be reversed: “God shall fight.”

The Jews believe that God shall fight for them.

That’s the Bible story of how Israel came by its name. Back to the archaeological story.

For two-hundred years after the split, according to Finkelstein and Asher, the Kingdom of Israel thrived and then its King, Hoshea, made a significant geo-political error of judgment. He double-crossed the rulers of the rapidly rising Assyrian empire. The king of Assyria, Shalmeneser V, invaded and destroyed Samaria and carried the tribes back to his capital, Nineveh, near modern day Mosul in northern Iraq and other places in his vast empire.

The ten tribes disappeared into myth, lost to history.

During this time the kingdom of Judah with its capital in Jerusalem was a backwater. How could it be a backwater if King David built an empire headquartered there and Solomon built the Temple in the city, forty cubits long, twenty cubits high of cedarwood overlaid with gold? According to Finkelstein and Asher that part of the story doesn’t fit the archaeological record.

There is little trace of the great cities of the Davidic kingdom. In their view, Jerusalem in David’s time was no more than a simple town on top of a hill. If you’ve been to Jerusalem and the surrounding area you will understand why.

Unlike the Galilee and plains of Samaria this region isn’t very fertile. Agriculture is hard on the steep, rocky outcrops of the Judaean hills. Few trade routes passed through because it’s difficult to climb up one sharp slope after another. But with the Northern Kingdom erased, Judah did finally begin to grow economically and refugees from the north swelled its population and brought the commercial skills developed in the centuries when the Kingdom of Israel was at its height.

Judah also became a client state of Assyria. But then a new power appeared in Mesopotamia: Babylon. The Babylonians overthrew the Assyrians at the same time Egypt re-emerged as a power pressing up on Judah from the south. If you are the king, which empire would you choose to ally with?

King Zedekiah of Judah chose Egypt—another incorrect geo-political decision. The Babylonians, led by Nebuchadnezzar, laid siege to Jerusalem and destroyed it and the Temple in 586 BCE. They killed Zedekiah’s sons in front of him, then blinded the king and dragged him into exile in Babylon along with Judah’s elites.

The story of both kingdoms, along with a chronological listing of the rulers, is related in the second book of Kings, and it jibes very closely with Assyrian records that survive. The Bible in remarkably terse fashion, lists the various king’s names and the length of each of their reigns with notation on whether or not they did evil in the eyes of God. Almost all of them did.

What was the evil that they did? Usually it related to rituals and worship. The Middle East in the millennium before Christ was a place of many Gods. Most empires were syncretic in their outlook. It was clever statecraft to allow a people you conquer to continue to worship the gods they always had. For rulers the main thing was that tribute from conquered territory arrived on time and there be no friction in trade from one region to the other. Imposing a new religion might have made that more difficult.

There was a lot of intermarriage between the various groups inside an empire. You might grow up with one set of gods and marry someone with a different set of deities and have shrines to both sets in your home.

The Hebrews were unique in having only one God and He was, in His own words, “a Jealous God.” The northern Kingdom however, as its trading relationships spread around the Middle East, became more and more syncretic, and after its destruction so too did the Kingdom of Judah.

Briefly in the reign of King Josiah, about fifty years before Jerusalem’s destruction there was a return to the old ways. The story is a scroll was found in the Temple, containing the covenant between the Hebrews and the one God whose name cannot be spoken aloud. Scholars think this scroll, found and then lost, contains the precepts and religious code of practice mentioned in the book of Deuteronomy.

A puritan fervor swept through Judah at this moment. But after Josiah’s death there was backsliding towards syncretistic worship and marrying foreign women. The people were conquered and their educated elites taken to Babylon where they hung up their harps and wept for what was lost.

When their tears dried they took up their writing tools and began to set down their national story. These authors created what we call the Old Testament and scholars call these people, the Deuteronomists.

They created a narrative crafted from oral traditions. Its purpose was to tell the story of the Kingdom of Judah and to zealously exalt Josiah’s view that Judah and the other tribes were “chosen” by the one true God. Their covenant explained by the story of the patriarchs, then slavery in Egypt, Moses, Passover, the Ten Commandments. Worship is centered in Jerusalem with the monarchical line of David raised above all others as prophesied by Samuel and its history related in the Book of Kings.

The books offered a constant lesson: those that deviated from the path of the one God, haShem (the name), would be punished, as happened in the forty year wandering in Sinai, the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel and finally, the Kingdom of Judah.

After fifty years of exile, in what must have seemed like a miracle, the Persian Empire swept out of the east and conquered Babylon and sent the exiles from Judah back to their land where they rebuilt the temple. They also began to be called Jews, derived from Yehudi, Judah-ites.

And the cycle began again, Jewish quarrels grew in relation to new hegemonic conquests. Should the people forsake the rules codified in Babylon from oral traditions to accommodate the demands of their new political masters? This is not a theological question but one of practical politics. Nevertheless the Jews could argue with each other about the choices they had to make.

The Persians would be driven back by Alexander the Great. Under the rule of the Greeks, a Hellenized form of Judaism would develop. Alexandria became a center of Jewish secular life.

Then the Romans conquered Judaea but had a hard time pacifying it. Rebels and rabbis made life hell for the legions. After each rebellion the hills would be covered with people crucified. One rabbi, Yeshua, an alternate spelling of Yehoshua, met this fate.

According to the stories told by his followers he argued with Caiaphas, the Jewish high priest of the Sanhedrin, as well as the Pharisees, a faction of religious thinkers. He argued with other groups of Jews until his death and then his followers carried on the argument. One of them, Paul, decided you didn’t have to be one of the chosen to become a follower of Yeshua, this syncretic idea, born out of a Jewish quarrel, became Christianity.

The argument over who is a “good” Jew is never ending. The Enlightenment movement towards religious tolerance, syncretism in a way, was outlined first by Spinoza. It was a natural evolution in his thinking that proceeded from his analysis of Biblical texts in translation and his understanding that the Book was not the literal word of God but a text shaped by human beings over centuries and in different languages. For this he was expelled from the Jewish community in Amsterdam. Bad Jew!

The history of modern Jewry is marked by this tension. In my book Emancipation I tell the story of Jews at the end of the era of ghetto-ization beginning during the French Revolution. How the tensions within the community over how much to maintain allegiance to traditional forms of worship and how far to integrate into Christian society by changing the mode of worship and forsaking dietary laws and intermarrying, spilled over into genuine quarrels.

Visit Israel today and it can feel like the two kingdoms are still in conflict. The syncretists on the beach in Tel Aviv, the puritans on the rocky hilltop in Jerusalem.

Today, the modern state of Israel is going through its greatest crisis since it was founded in 1948. Even before the Hamas atrocity of October 7th, in the huge weekly demonstrations against the Netanyahu government it was possible to see the terrible habit we Jews have of quarreling amongst ourselves to the point that it threatens our own existence.

The demonization of those who have long argued for a two-state solution as a way of dealing with the Occupied Territories was already ugly and ruinous. The continued presence of Netanyahu as Prime Minister was already splitting Israeli society. Many of us, especially the secular ones, unironically see him as doing evil in the sight of the Lord.

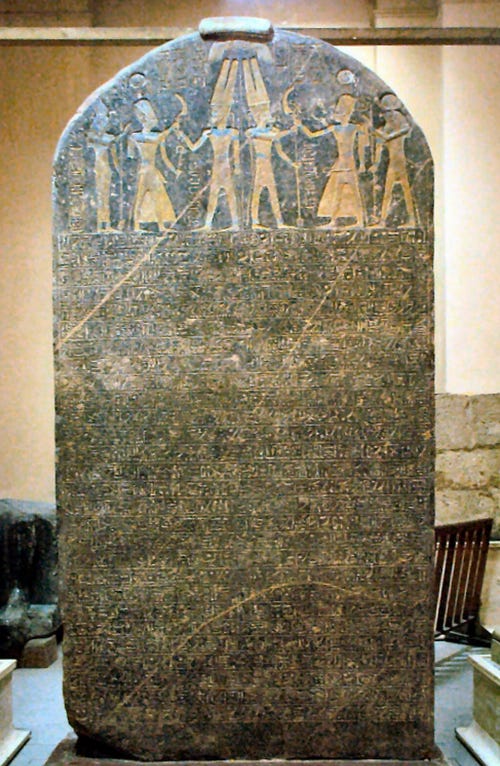

And I worry about the recurring patterns of Jewish history. Patterns established long before the land was called Palestine, going back to the time before Jesus and before Alexander. I shake my head when I think about the first mention of Israel in the historical record, on the Merneptah Stele, a tablet recounting an Egyptian pharaoh’s victories created in 1208 BCE:

Israel is laid waste, its seed is no more.

Thank you so much for presenting what is a difficult and complex history/theology of a people rooted in this particular place on planet earth. I wonder how you understand the whole matter of the "settlements" built on "occupied territories" and the matter of Jewish settlers? The past 75 years seem to need explication. When stitched together with the horrors of pogroms and the horrors of WW2 and the many other violent atrocities perpetrated by one or another group of people on another group labels of any kind are not helpful. There is a very important conversation however going on related to the matter of colonialism, past and present, where one group displaces another. The term "settler colonialism" is a term used by Native Americans to describe how the lands they occupied for millennia before European colonists arrived on these lands. Maybe we cannot dispense totally with the concept "settler colonialism", which describes a current reality affecting descendants of all those Palestinians who were dispossessed beginning in 1948. What keeps surprising me is that Palestinians are adherents of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. I would imagine there are some Palestinians who would say they are secular and belong to no religious group. This article is so rich, I need to read it a couple more times to digest it. My personal hope is that from this terrible horror of 7 October and all the violence and revenge that has followed a way will be found out of the terrifying wilderness of pain .,loss, and hatred.

Blood for land. River to the sea. Whose slogans are these? Could go either way.

The End of Biblical Studies by Hector Avalos gives a different perspective on Biblical wisdom. Bart Ehrman disassembles the New Testament fairly decisively and the constant haggling over Old Testament does an even better job of self immolation than real academic study might. The Bible Uneathed answers many questions of Biblical history with a negative. The Israeli government has worked tirelessly to find proof of the stories in the Old Testament with little to show. Yes, there is a history of many Jewish settlements in this area but the veracity of heroic or outlandish oral histories are rightly questioned.

These are asides to the issue of why the use of force to expel people from their homes is accepted without question in the modern era. Creating a Jewish homeland in Poland or Germany or Russia was as awkward in 1946 as it is today. Montana was out of the question. The Shoah now has a long dark shadow in the land claimed by God for arguing. Many hearts have been blackened by the bloodthirsty grip of various monotheisms. The Koran offers little hope. Israel and Palestine have become definitions for argument and disagreement for the world, unfortunately. Perhaps the Saudis will guilt/whitewash finance a new Palestine. Not. Nothing new here.

Us antitheists need to stick apart, as always. Take care Michael.