In science, many great advances come from anecdotal observations that arouse an individual’s curiosity. The anecdote leads to an enquiry and then a breakthrough. Think Alexander Fleming, returning from his summer holiday and noticing a mold growth in an accidentally unprotected petri dish in which he was growing staphylococcus bacteria. The mold had killed off the staph bacteria. He investigated why. The world got penicillin.

In social science, today at least, that doesn’t seem to be the case. There are reams of data collected and then questions asked. Certainly that is what happens with public opinion polling. Society is divided into categories and then voters shoe-horned, with the help of institutional journalists, into them.

But even though society doesn’t really conform to these categories, Americans inform themselves via this statistical short-hand. I’m not sure it is the best way to go about understanding what is happening in the country as the US approaches Election Day.

This is an example of what I mean. By any data measure, the US economy under President Joe Biden is going gangbusters. It has recovered all the ground lost during the covid shock (which was mismanaged by Trump) and weathered the inflationary storm that followed Biden’s decision to pump up the economy as a way to re-start it after the pandemic recession which was followed by leading oil producing countries bumping petroleum prices in 2022 to make up for revenue lost during Covid.

The estimable Heather Cox Richardson’s substack from October 11th provides a summary of the good news:

A report from the Labor Department yesterday showed that inflation has dropped again, falling back to 2.4%, the same rate as it was just before the coronavirus pandemic. Today the Dow Jones Industrial Average jumped 400 points to a record high, while the S&P 500 closed above 5,800 for the first time.

Washington Post economics columnist Heather Long noted that “[b]y just about every measure, the U.S. economy is in good shape.” Inflation is back down, growth remains strong at 3%, unemployment is low at 4.1% with the U.S. having created almost 7 million more jobs than it had before the pandemic. The stock market is hitting all-time highs. Long adds that “many Americans are getting sizable pay raises, and middle-class wealth has surged to record levels.” The Federal Reserve has begun to cut interest rates, and foreign leaders are talking about the U.S. economy with envy.

Yet, most American voters, until the last two weeks thought that Trump was better placed to handle the economy. Why?

Anecdote:

This headline, reporting a fact, appeared on Friday.

In the “information” overload that characterizes contemporary society, that headline might well cut through all the solid statistical data about the condition of the economy. A significant number of voters may simply not believe the broad statistical data but fear their jobs will be going next. If Boeing is laying off 17,000 workers other companies are sure to follow, would be what these voters are thinking.

This disconnect between positive data and society’s response is not new. I observed it throughout the 1990s on my occasional rambles through the US for the BBC (which form the core of part 4, Road Trips in Flyover Country of my other substack, History of a Calamity).

One of Bill Clinton’s favorite one-liners as he campaigned for President was, “If you want to live like a Republican, you need to vote Democrat.” And the economy under Clinton was by statistical measures solid. But in the Midwest, the South, and along the Border, the improved economic conditions didn’t seem to be shaping people’s experience of the world.

Two generations of American workers are living with PTSD caused by the rapid de-industrialization that started with the Oil Shock of 1973 and accelerated through the 1980s and Reagan’s presidency as unions were demolished.

PTSD is not too hyperbolic a description of the trauma of losing a full-time job.

Here my anecdotal evidence is personal: I was laid off from a staff job in journalism in 2005 at the beginning of a major downsizing of the news business. Data varies but estimates are that 40% of newsroom jobs went in the three years following my own lay-off. I have never had full-time salaried employment since and have lived in a precarious economic state (which is the reason I started this substack and ask you to take out a paid subscription).

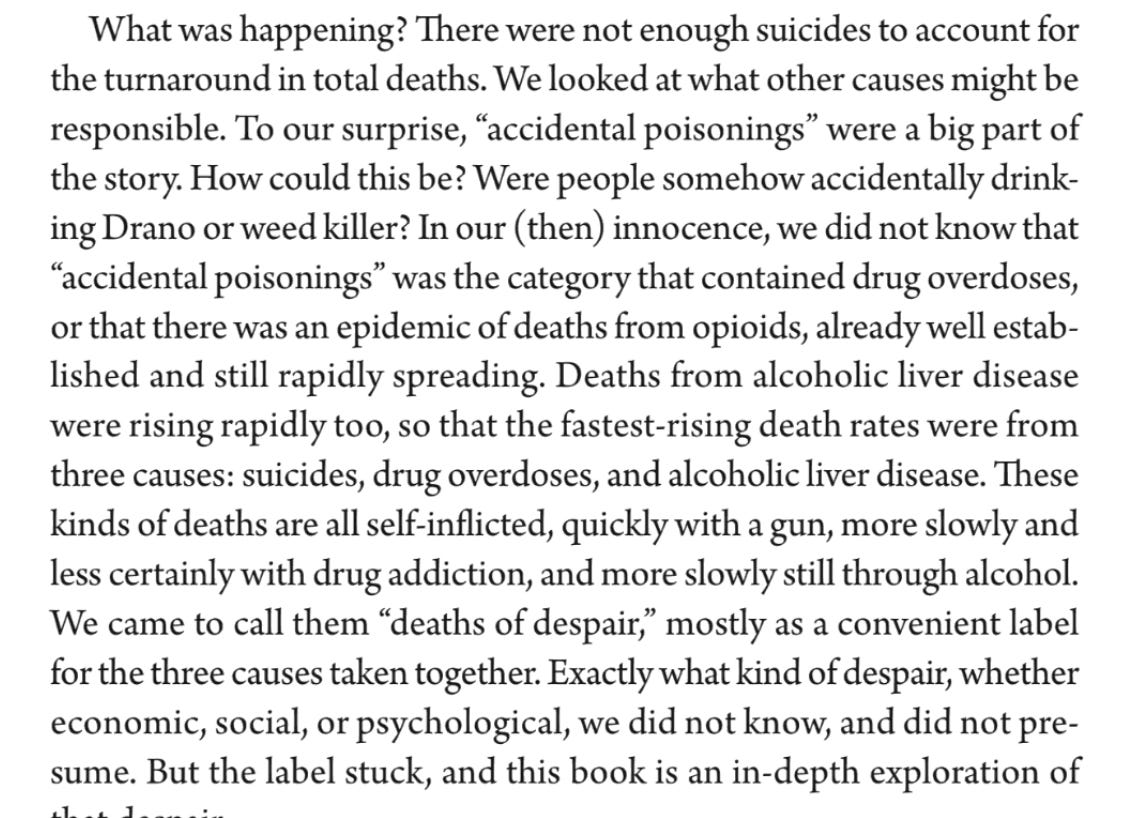

My experience led me to read the work of Princeton economists Anne Case and Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton, whose approach to their work is closer to Alexander Fleming’s than an election pollster’s. The pair saw a trend in the data, death rates were rising rapidly among middle-aged white people. So they investigated what was behind this unexpected rise and they wrote a book called “Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism”. This paragraph from their introduction summarizes my point nicely:

The creation of what came to be called the “precariat” in this century is a shock still being dealt with. There may be social scientists measuring how this affects society and in particular voting patterns but I don’t know of any. When I read election polling stories in the mainstream press I see voters are broken down along racial and ethnic lines and by age groups but not by how many lay-offs they’ve had, or have occurred in their families in the last two generations. If you have seen polls or just research on how this affects voting patterns, please contact me.

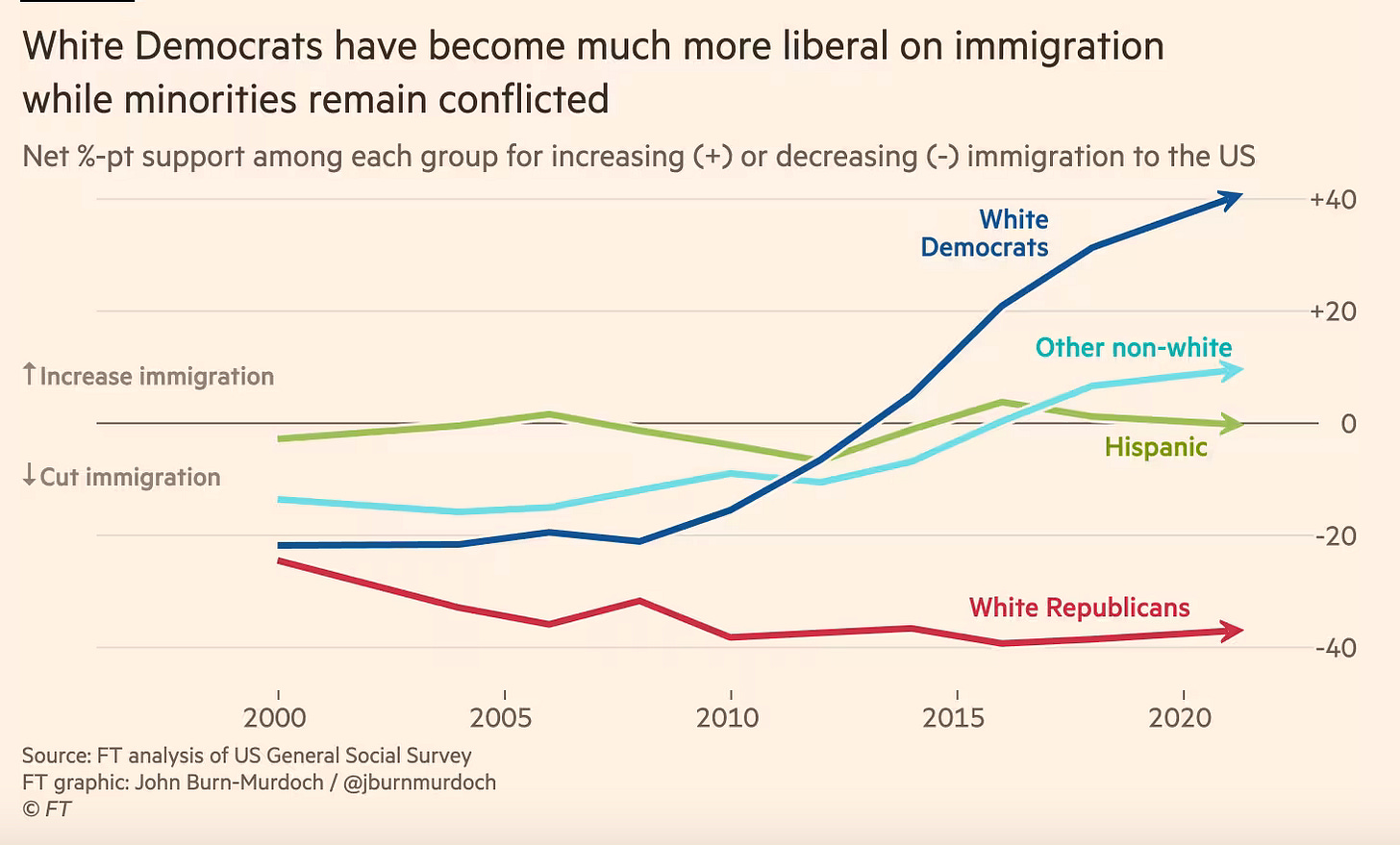

Here’s another, bit of data that anecdote preceded, it’s from an article this week by the Financial Times’ data columnist, John Burn-Murdoch

Murdoch points out that in last May’s UK election,

“Labour won less than half of the non-white vote for the first time.”

His article then focuses on what is happening in the presumed coalition at the heart of the Democratic party: University educated whites and minorities.

Again, this has been clear anecdotally for a long time. During the midterm elections in 2018, I spent time in Texas’ 23rd congressional district a border constituency running between El Paso and San Antonio and found many Hispanic voters all in for the Republicans. Why? racism they could handle, but they had moved heaven and earth to get out of Mexico and didn't want the troubles of that benighted country following them over the Rio Grande.

There is another anecdotal reason I have discovered over the decades: blanket "social justice" campaigning has no appeal to people just at the door of the middle class and who can't pass the threshhold if government raises their taxes to pay for social programs, or if you open your borders so that new arrivals can undercut them on salary. Throw in some of the wilder causes included in the category "social justice" and you will lose votes.

When I’ve used the word anecdotal in this piece I’ve obviously intended it to mean “in my experience” as a reporter and as a person. I wonder what the life experience is of the generation of reporters currently holding staff jobs at the main institutions of American journalism?

The anecdote here, the “in my experience” observation, is one of the least remarked changes of the last 50 or so years in journalism has been the institutional newsmedia requiring reporters have an advanced degree in journalism as the entry ticket to a career. It also helps to have done your undergraduate work at one of the elite universities if you want to make it to one of the big institutions like the New York Times or one of the networks.

I did neither. At an age when people go to J-school, I was driving a cab on the night-shift in the burning New York of the 1970s and by day failing catastrophically as an actor. Those experiences did more to prepare me for reporting on people living through conflicts, or just talking to people not of my original social class. I suspect that social class is the same one as most of today’s young journalists going from elite higher education to elite journalism: Upper Middle.

But let’s eliminate suspicion, let’s get some data about who was educated where at the big institutions of the press and what socio-economic background did they come from? Are they overwhelmingly upper middle class? How does that affect their understanding of the world and in turn, does it lead to an over-emphasis of the same social justice issues that the data in John Burn Murdoch’s FT piece demonstrates is costing Democrats support among traditional parts of the Democratic coalition?

And does this, as I suspect, very narrow sub-group of American society have enough real world experience to understand the world in which their fellow citizens live without reducing them to numbers, mere data points on a grid?

As you can tell, I prefer to meet people and talk to them rather than reading a spread-sheet, which is why I am asking for your help to travel to the US, specifically Georgia and North Carolina, to report on the final furlong of this election and the days after, when the counting of the vote promises to be tense. There are two ways you can help me do this:

TAKE OUT A PAID SUBSCRIPTION

great article Michael - the point about Latino voters in Texas wanting the wall is just one of many clarifiers in this - I remain trembling in my trainers - good travels