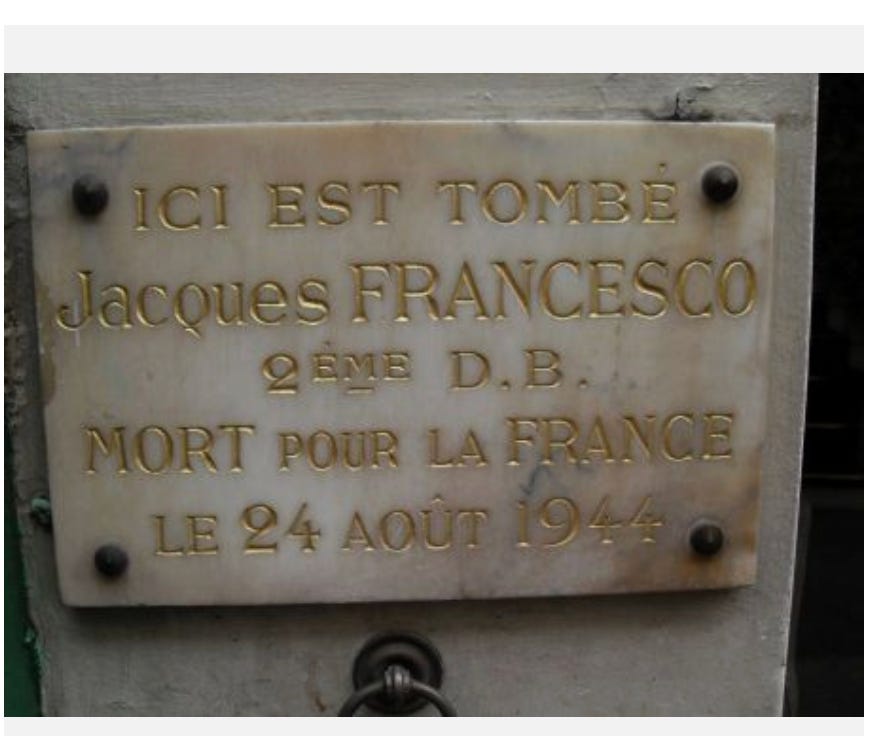

There is a place I visit whenever I’m in Paris. Not a museum, or a restaurant, or bar, or a place I kissed a girl. It’s just a small memorial plaque on a wall:

There are memorial markers like this all over the French capital but this is the one that I recall. Partially because of its location, the Hotel La Louisiane at the intersection of the Rue de Buci and Rue de Seine, the heart of the 6th arrondissement, St. Germain des Pres.

As a student and well into middle age this intersection was a major axis of my Parisian life and quite possibly yours when you’ve visited the city. It’s the location of a bar, La Palette, very touristy now but less so 50 years ago. La Palette was the arrival and departure point for rambles down the Rue de Seine, through a small covered archway in the Mazarin and then over the Pont des Arts to the Louvre or further on into the Right Bank. Rue de Buci with its market was a place to pick up stuff for a picnic or the train journey back to London.

On one of those rambles I first saw the plaque and have walked past it frequently over the decades. To pay homage

This is the main reason. Look at the date: it was the last full day of fighting for Paris’s liberation from Nazi occupation and this man, Jacques Francesco, would have been among the last to die in that battle. Knowing nothing about the man commemorated on the plaque I vividly imagined him in those circumstances.

I have been in urban warfare, the streets empty and ghostly quiet. There is a particular sound gunfire makes in enclosed streets where all other city sounds are absent. It not only cracks and whizzes but echoes and you can hear the impact of bullets on masonry and concrete. The limestone of which much of Paris is built and the narrow scale of its ancient streets would only amplify this effect. Francesco would have heard the battle coming towards him and the fighting as far away as the other side of the river and the Louvre because of the echo effect.

I made up stories about him. I wondered if he had died instantly or had he been wounded and sufficiently conscious to know that Paris was on the verge of liberation but that his wound was a mortal one and he would not live to see it. Perhaps, he was separated from his unit, and encountered a squad of Germans, wounded, and then jacked up against the wall where the plaque is and summarily executed with the last thing he heard in this life the sound of victory so close.

In any case, I am rarely in Paris in August but I do try and think of this brave man at this time of year and since this is the 80th anniversary of his death I decided to do a little research to see if in the ever expanding world of online knowledge there might be a way to find out about him. There was, and this is what I learned:

My imaginings are impossibly romantic, his story speaks to the historical reality of war’s chaos. The plaque is inaccurate in every respect, starting with his name. The man commemorated was baptized Auguste Fenioux.

He had a younger brother, Francois, and he took that name Francois/Francesco for his nom de guerre. He was already in the French army when war broke out, escaped to Vichy and then to North Africa where he joined the Free French Forces under General LeClerc.

In the battle to liberate the French capital his group was assigned to clear the area around the intersection of the Rue de Buci and Rue de Seine on August 25th. The date on the plaque is also wrong.

In any case, 80 years ago on that day, there were French milice (Nazi collaborating paramilitary force) sniping from the rooftops.

Auguste Fenioux/Jacques Francesco was shot in the chest just outside the Hotel La Louisiane. (more on this historic hotel’s role during the war and the years after can be found in Agnes Poirier’s wonderful book Left Bank).

It would take years for Fenioux’s family to uncover the mystery of his death and make the case for recognition. His nephew Claude has begun a book about him based on research. I found this extract via google. His imagining is obviously closer to the truth than my naive ones.

In the early morning, the Captain had distributed to each of his soldiers a packet of cigarettes and a half-litre of cognac. The sky was azure blue, without a cloud. The heat was beginning to be stifling. On Rue de Seine, Private First Class Ardan stretched to his full height. He put his rifle in his left hand. A bullet bent him in two. The noise of the tank that he was escorting with his section had partly covered the sound of the shot. Corporal-Chief Auguste Fenioux, who was ahead of Ardan, immediately turned around and rushed towards his comrade, crouching down next to him.

“It started from up there, from the roof, on the left,” cried the wounded man, his hand clenched on his side. “Milice, I'm sure, there must be several of them! Watch out! I was hit in the side, but I think it wasn’t too serious…

As he looked at his blood-stained hand, he didn’t have time to say more. Another shot was heard and Fenioux, who had raised his head and turned around, fell in turn.

“Gus,” Ardan shouted in a cry of pain and rage, “let’s take cover, we’re going to get shot like rabbits!”

Struck by a bullet in the chest, the corporal collapsed. Right in front of number 60 where Juliette Gréco, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir lived, on the corner of rue de Buci. It was 11 a.m. Immediately taken to the nearby Laennec Hospital, Auguste Fenioux died there at 1:50 p.m. He was twenty-eight years old.

The farther in time we get from the war the more difficult it is to understand the courage of ordinary people living through it. Learning more about this man, the fact that he was a professional soldier in battle, not a former high school teacher, fighting as a guerilla to rid his country of a fascist invader does not change my understanding of the circumstances of this man’s death. The battle was effectively won. Yet he carries on to the last.

It is worth reflecting on this 80th anniversary of the Liberation and on any other day is would you, could you be this heroic — just for one day.

Thank you, Mike, for this terrific look back at a time so clearly relevant to our own. Applying your well-honed skills as an on-the-scene reporter brings it all alive once again.

Again, thanks.

Reading your excellent piece makes me think, as I always do, why didn’t I when I still had the chance ask my father more questions about his experiences from D Day all the way to Berlin? I had so many years in which to do this. I have a few photos and a few stories but know hardly anything really.